To John Lautner, for relentlessly pursing his vision and fighting for his craft.

Driving down the road of life in your 1960 Plymouth Fury, you feel like you have everything you need: cash in your wallet, your sweetheart by your side, possibly a couple kiddos in the backseat. But this is the atomic era—the economy is bustling, consumerism is the rule, and deep down, you want more…because you know you can have it.

“More” is in abundance in mid-century America. It’s everywhere you turn—on your television, in your neighbor’s house, his carport, his backyard…and you want it. You’re human. So you’re driving, searching, trying to make the best decision as to where to exchange that cash in your wallet for the products you want, because you glance to your sweetheart…and she’s worth it.

This is where ad man Don Draper comes in, because he has multiple sweethearts, and they—as a whole—are worth a lot to him, too. In order to lavish upon his collective sweethearts what they want, he first has to convince you to do the same.

Is this tale about capitalism? Absolutely, in a fantastical, romantically spun fashion. It’s also about Americanism. Our culture of a free market economy with purchasing choices and opportunities for commercial improvement or decline is undeniable. And, although you may not be familiar with the term, this tale is about Googie—an extreme, often audacious, architectural style with the raw function of provoking a quick decision to exchange goods or services for dollars.

By bringing Mr. Draper into the story I’m not suggesting Googie was a creation of Madison Avenue. I’m simply defining it as advertising, which, at its most basic, functional level, it is. The purpose of Googie was to grab your attention and quickly convince you to turn the steering wheel of your Plymouth Fury into a convenient parking lot. However, Googie was not formulated at an ad man’s conference table, but rather an architect’s drafting table.

“Googie” (pronounced ‘goo-gee) was the family nickname for Lillian K. Burton, the wife of entrepreneur, Mortimer C. Burton. In 1949 Mr. Burton erected a coffee shop in West Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard and honored his wife by naming the establishment Googie’s.

One day in the early 1950s, architecture critic and magazine editor Douglas Haskell, and architectural photographer Julius Shulman, were driving along Sunset Boulevard. Upon spying Mortimer Burton’s coffee shop, Haskell demanded the car be stopped, then proclaimed, “This is Googie architecture.” An article with that as the title, written by Haskell, ran in the February 1952 issue of House and Home.

Haskell made no attempts to hide his ambivalence regarding the emerging style. “It starts off on the level like any other building,” he wrote. “But suddenly it breaks for the sky. The bright red roof of cellular steel decking suddenly tilts upward as if swung on a hinge, and the whole building goes up with it like a rocket ramp. But there is another building next door. So the flight stops as suddenly as it began.”

The architect of Googie’s coffee shop, John Lautner, was not mentioned in this specific article by Haskell. Lautner was a student of famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and followed Wright’s ideals of functionality and innovation, grounded in the organic. In the mid 1940s, before Lautner designed Googie’s, he designed three Coffee Dan’s, coffee shops all located in Southern California. His work gave birth to the Coffee Shop Modern Style, incorporating “the eye-catching roofline, the integrated sign pylon, [and] the destruction of the distinctions between indoors and out.”

In “Googie Redux: Ultramodern Roadside Architecture,” Alan Hess explains that the Coffee Dan’s designs display “Lautner’s combination of structure, space, and function. To Lautner, human predilection, not structural requirement, should shape a space. The cantilevers, structural bents, and concrete shells made possible by modern engineering free him from having to fit humans into the boxlike rooms created by conventional building methods. He selected the vaults and glass walls and trusses and angles of his buildings to help him shape the concepts of space he favored. This uncompromising attitude made him one of the true purists, sweating out the design to the last detail to preserve the consistent idea.”

Form following function…

Midcentury America hosted the merging of fresh, enthusiastic ideas with exciting innovations. Prevalent and affordable automobiles steered the culture, fueling the desire for suburban tract housing and shopping centers. Returning war veterans were eager to start families, to retool wartime factories for domestic progression, and to push the American dream onward. Peacetime enthusiasm had everyone looking to the future and to space. Everything was forward and upward. And sometimes even at a diagonal.

The new challenge for businesses was that consumers weren’t walking on sidewalks peering up at merchant names on store fronts or gazing into their windows. Inside, shoppers whizzed by in their cars, distracted by other automobiles and pedestrians. Businesses had to attract buyer’s attentions from a block away and clinch it. The solution was for advertising and building structure to become big and loud and flamboyant. Additionally, it had to speak the language of the day, and that language was futuristic…space.

Rockets, amoebas, boomerangs, chevrons, starbursts, and atomic models, not to mention bold geometric shapes and angles and vivid color…this was the cultural dialect of post war America—the atomic era. American business quickly learned to speak this emerging language, and created some fun and unprecedented art as a byproduct.

Googie is better shown than described. After all, the purpose was for it to first catch the eye, then excite the mind. So I’m displaying several examples, all from my hometown of Topeka, Kansas. Even though the style was rooted and prevalent in Southern California, architectural examples of the atomic era are sprinkled all across American. How fortunate we are that some pieces are being used and maintained, time capsules of the American vision of the future, over fifty years ago.

Auto Acceptance Center, 29th Street. The folded plate roof captures the eye and draws it upward.

Alorica, 29th Street. Originally a Katz Drug Store, I really dig how the blue underside of the folded plate roof accents its zig zag.

Bobo’s Drive In, 10th Street. A Topeka Classic since 1948, their red neon signs and wall of glass are period Googie, and their shakes are delicious!

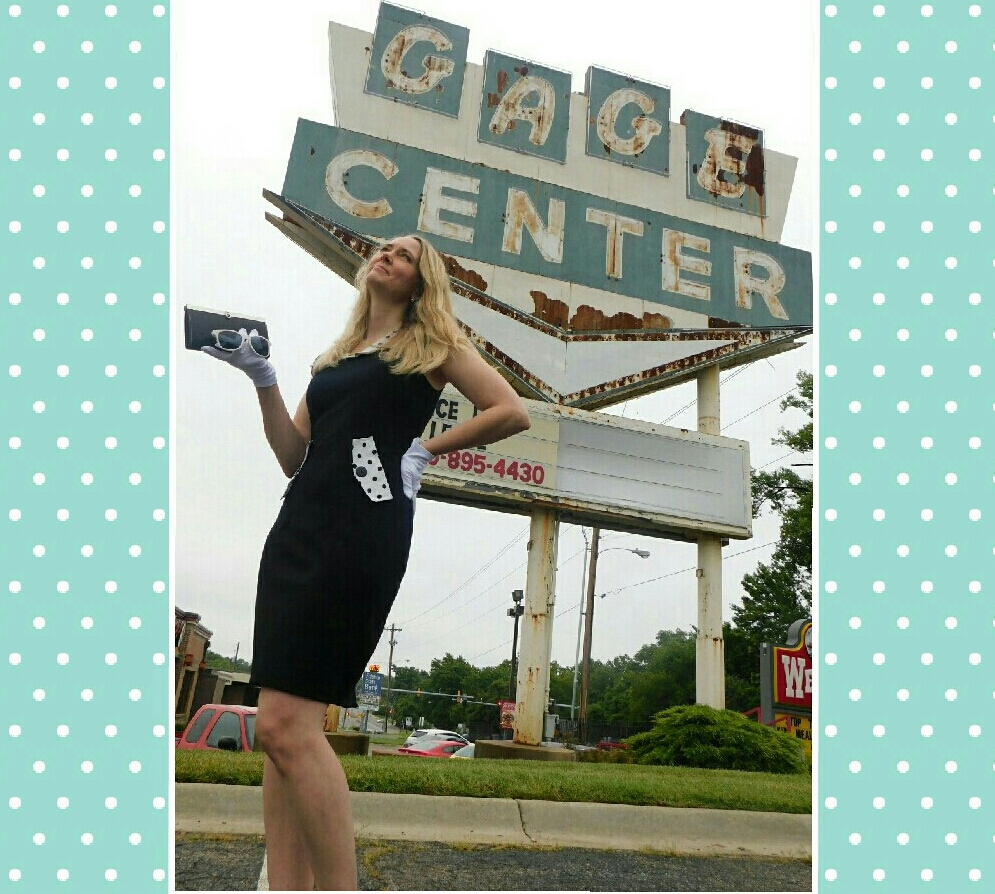

The Gage Center sign off Huntoon Street and Gage Boulevard is 100% Googie. Large, bold, colorful–wildly geometric including a slender chevron. One of my favorite architectural pieces in Topeka.

Gage Bowl, Huntoon Street. The zigzag of the folded plate roof appears to float above the entry.

Soon to be Mr. Nice Guys, Huntoon Street. Obviously this was a mid-century drive-in. Note the subtle boomerang (folded) roof line above the parking spaces.

Topeka Dental Associates Building, Huntoon Street. Love the wavy, concrete shell, vaulted roofline and floor-to-ceiling glass windows.

Chief Drive-In sign, 37th Street. Kudos to Wal-Mart for not only saving but preserving this beloved piece of Topeka architecture.

Central National Bank, Quincy Street, downtown. Towering stucco arches supporting a round protruding eave. Two stories of solid glass…I’d mark this structure down as Googie in my books.

Hanover Pancake House, Kansas Avenue. In business since 1969, this sign can’t be missed. Note the colorful diamonds tracing the building’s eave.

Spangles, Wanamaker Road. Founded in 1978, Spangles incorporates elements such as neon, bold colors, and geometric juxtaposition. This particular restaurant was probably built around 2005, yet its heart is mid-century.

University United Methodist Church, 17th Street. The structure and roofline angles forward as it reaches to the heavens.

Gage Bowl sign, Huntoon Street. Googie architecture often tilted letters about, such as “fun” was placed, above. The bowling pin bursts from the base of the sign, a common geometric element of Googie.

Kansas Children’s Discovery Center, 10th Street. This building is approximately five years old yet it screams Googie. The impressive triangular roof, supported by walls of glass and colorful poles, mimics a rocket ready to launch.

Did you notice this post contained a fair bit of ice cream? I’d argue that Googie is the ice cream of design—a tall, swirling, scrumptious ice cream cone. It climbs upward to the sky because no one said it couldn’t. With the aid of post war building materials—sheet glass, glass blocks, metal, plastic, stucco, wood, copper—the wafer and the ice cream merge and harmonize.

There were no rules regarding Googie materials or geometry—this cone twists, dollops, scoops, and curls in any flavor imaginable. It not only brings your eye up and out and to the diagonal but brings it deep into your imagination. You’re seeing man’s past, present and future, all at once, in a single, delicious dessert.

And what better treat for your sweetheart who’s smiling at you from the passenger seat of your Fury and the for the kiddos in the backseat than a tasty bit of ice cream.

Now that you know what Googie is, send me a pic of it from your city. Email it to crkennedy3@gmail.com or…hashtag it as #avcgoogie on social media. Make it a selfie. And have fun. Because Googie is nothing if not fun!

Ice cream makes everyone happy. So does Googie!

Sources:

Hess, Alan. Googie Redux: Ultramodern Roadside Architecture. Chronicle Books, LLC. 2004.

Leave a Reply