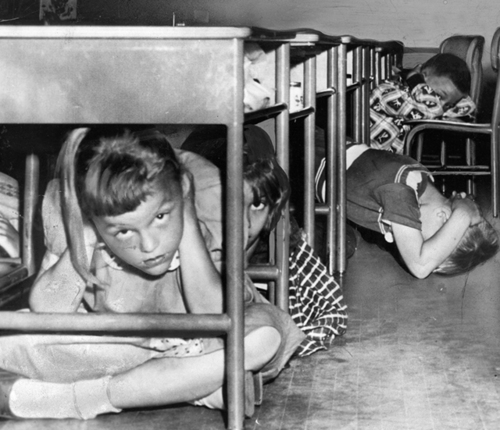

For the children who became known as the baby boomer generation… During civil defense drills, while you were curled up in a ball under your school desk, did you ever consider that Santa was watching?

The fear in her eyes puts tears in mine.

As a kid I was never once instructed on how to “duck and cover” under my school desk. I guess at that point in the Cold War, during the 1970s and 80s, America’s fears had thawed regarding a nuclear weapon being launched by Soviet Russia. Or more likely, educators and the Civil Defense Administration were in a new position, caught somewhere between the perceived ridiculousness of the practice and the political fashion of the day.

Even as early as the late 1960s, America’s fears and fascinations with all things atomic had decayed. The mid-century lust for conquering space by progressing science, which went so far as to bring representations of starbursts, parabolas, and atomic symbols into our newly constructed, suburban tract homes, also fell out of fashion. This period of history, which began in 1945 with the detonation of the first nuclear bomb, became known as the Atomic Era. By 1965 its lure had peaked and was rapidly cooling.

A few months ago I realized I needed a couple Christmas stockings at my 1953 Cape Cod home, and, of course, only mid-century stockings would do. I hoped there were still a few still hanging around from the 1950s that screamed “Atomic Era.” I scoured eBay and the Internet—surely the supreme coolness and innovation of the mid-century aluminum Christmas tree spilled over into other decorative traditions of a mid-century Christmas celebration.

Apparently it hadn’t. I found nothing that satisfied my atomic craving. My enthusiasm briefly went cold, much like a hard lump of coal. Once again, I was forced to revert to what has become a perennial Plan B in my life: if you can’t find what you want, create it.

But how do you craft a nostalgic representation of something that never existed? Was it even possible? A bit of research and several attempts at the drawing board finally took me there, and I began with a visitation of why the atomic era was so “atomic.”

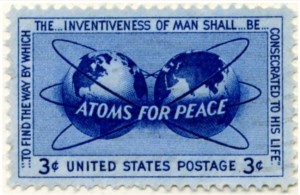

“Atoms for Peace” was the title of a speech delivered by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on December 8, 1953. He was addressing the UN General Assembly in New York City as part of the media campaign called “Operation Candor.” The idea, arguably propaganda, was to enlighten the American public on the risks and hopes of a nuclear future.

At first glance, I was shocked by the idea that atomic fission should be consecrated.

Not only were early Cold War Americans fearful of the Russians dropping the bomb on us, but also of what our own government might do with its powerful arsenal of nuclear weapons. Eisenhower’s plan was not only to manage the emotions of the America public but to evoke the containment strategy against Russia—to stop the expansion of communism. The scenario reminds me of Uncle Ben’s often-quoted line to Peter Parker in the Spider-Man movie: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Eisenhower hoped to squelch national fears and reassure its citizens of a scientifically progressive yet militarily level-headed U.S. government. Atomic energy—the result of nuclear fission—was to be used for good, not evil. Convincing the Russians to do the same was an obvious diplomatic mission. Sustainability of the human race and any chance for lasting peace depended on it.

Mid-century design for peace…The preoccupation and alarm of atomic energy and its manifestations drove the post-war culture, but not only to build fallout shelters and practice air raid drills. In a mid-century paradox, the atomic symbol and its scientific cousins wove themselves aesthetically into the period’s design, often found in architecture, automobiles, and perhaps more abundantly, interior design.

After splitting the atom and winning a world war, America’s confidence rode high, and we were enthusiastic to conquer space. We stamped that fervor into entertainment, children’s toys, and the basic elements of our lives—the simple yet essential components of our homes. Mathematic and scientific representations such as parabolas, starbursts, and amoebas were incorporated into the look and construction of interior design enhancing futuristic and progressive flare.

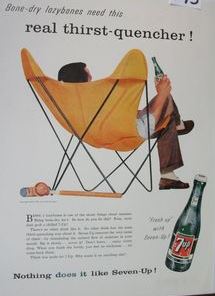

The atomic symbol fit neatly into the evolving mid-century style, easily found in the form of wall clocks and light fixtures, and less obviously in the slender, arching, metal legs on tables and chairs. Those thin geometric lines, appropriately known as a “sensitive line,” gave furniture the appearance of gravity defiance.

Seven-Up ad featuring the Butterfly chair. The sensitive lines (the chair’s metal legs) resemble the atomic symbol.

According to Thomas Hine in Populuxe, the theme for the period was dynamism and fragmentation. The scientific, industrial, artistic, and economic systems exploded in post-war America. As a result, people moved out from the city core and created their own small sanctuaries in the suburbs. Bringing symbols of the atom into these new homes—their isolated space for refuge and peace—seems a contradiction. To lounge in a chair with atomic shaped legs and glance at your atomic clock, while only mere feet from your bomb shelter—an arguable necessity due to fears of atomic weaponry—is a fascinating mid-century paradox.

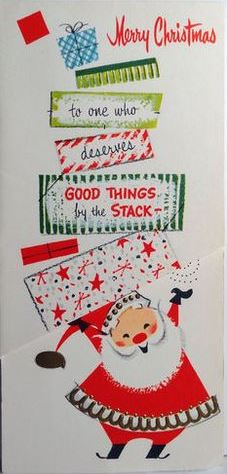

Santa for peace…A sleek, linear Santa Claus made a bold appearance in atomic era design. He jetted across Christmas cards in rockets and spacecraft, propelling American faith that we could get there, too. He carried his traditional optimism in the modern craft of his choice, and still toted an array of presents, even though the American landscape for materialism had vastly changed.

By the 1950s he was firmly established in American culture and acting as a convenient conduit for the exploding post-war phenomena of consumerism. Could there ever be a better advertising spokesman for frivolous consumption than Santa? The era of economic boom, mass production, and constant upgrades for progress used Santa as a well-suited vehicle to promotion and push products out of the suburban retail stores and under the manufactured aluminum Christmas tree.

Santa was all over the scene in mid-century America—appearing in pre-holiday parades, on Christmas cards, in newspaper advertising inserts, on mugs filled with hot chocolate, in seasonal yard art…not to mention in department stores, where Santa could cleverly ask an innocent child what he or she desired as a Christmas gift. How often was that object within proximity of Mommy and conveniently located near a cash register?

A three-year-old on Santa’s lap in a Virginia Department store, circa 1961.

The child appears to be a bit fearful as to his status regarding The Naughty and Nice List.

This cynical view of Santa is merely a portion of his complex and long career. His rich history includes fourteenth-century accounts of teachers dressing as St. Nicholas on December 6th and using a birch rod to beat the children who failed academically that year, while rewarding successful children with sweets or pocket money.

A much kinder mid-twentieth century Santa continued to analyze the behavior and enforce discipline upon children. The 1934 song, “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” enjoyed its most popular versions in 1951 recorded by Perry Como and 1953 by Gene Autry. Listeners were reminded: “He’s making a list and checking it twice, Gonna find out who’s naughty and nice.”

Santa’s mid-century career mirrors that of another 1950’s global power and icon, if you will. He’s acting much like Eisenhower, who hoped to advance industry, keep the peace, and promote responsibility. Santa, similarly, is balancing the desires to produce and distribute material goods with the need to keep people, mostly little people, accountable for their actions.

Santa had a lot to juggle in post-war America.

Believing for peace… Last week my fourteen-year-old daughter nervously approached me and told me she had something important to tell me. Several scenarios quickly ran through my head, none of them comfortable conversation topics. But what she professed I had long been ready to combat, with a reply that was sincere in my heart and ironclad. She wanted me to know that she knew Santa wasn’t real, and I didn’t have to get her any gifts from Santa. I sensed her confession was less out of blossoming maturity, and more from economic concerns—she wanted to save her mother a buck. I appreciated that.

No way is this beautiful two-year-old going to grow up and stop believing in Santa.

Unfazed, I held firm to my position. My response had nothing to do with me trying to cling to my baby’s innocence and everything to do with a ridged personal stance. I didn’t hesitate to tell her I still believed in Santa, and my advice to her was to never stop believing. She probably internally rolled her eyes at me, but I hope I at least planted a seed in her strong-willed mind.

I really do believe in Santa Claus. For all that Santa has represented over the centuries, to me his strongest attribute is the sense of hope and calm he casts during what has become a frantic and stressful season. Santa grounds us in the foundation of Christmas, in charity and sacrifice, which is the pure definition of love.

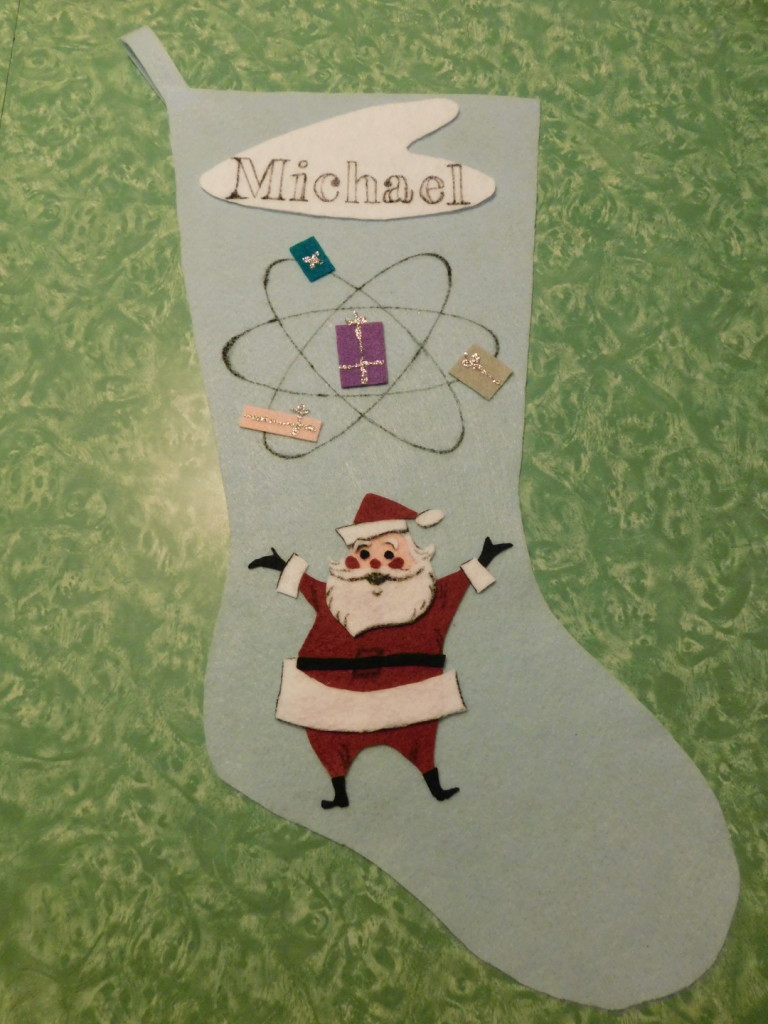

So Santa Claus, an undeniable mid-century icon, became the foundation for my atomic stocking. Many of the images of him from the era, mostly on Christmas cards, depict him holding up a tall stack of wrapped packages. It’s as if during that time in history he was considered to be carrying a heavy load.

Mid-century Santa Christmas card

As my mind struggled with exactly what Santa should be doing, and debated if holding up packages had any mid-century significance, those packages began to weightlessly swirl over his head, as if he were juggling them. Perhaps they simply defied gravity.

Although I couldn’t find the perfect stocking on eBay, I did manage to score McCall’s stocking pattern #2271 from 1958, which I think lent authenticity to the cut of mine. Besides Santa and his inventory of presents, I also mixed into my design period-appropriate motifs and a handful of mid-century colors, including pink, gray, and sky blue. If I can get the back of the stocking sewed on before Christmas Eve, Santa and I can continue our long-standing contractual agreement.

I don’t know how many times the little boy from Virginia pictured above had to “duck and cover” under his school desk, but I’m pretty sure he never hung a Christmas stocking with sensitive lines depicting the atomic symbol or which fashioned an inscription of his name. Somewhere in his youth, however, he perfected the talent of comedic timing, as he told me this joke as I was wrapping up this blog. Why should you never trust atoms? Because they make up everything. Apparently they do make up everything, even contemporary depictions of non-existent, mid-century, atomic Christmas stockings.

Promoting economic expansion through consumerism while incentivizing scientific responsibility in our world leaders is a big job, but leave it to Santa Claus to juggle it effortlessly.

Sources:

“Atoms for Peace”. Wikipedia. N.p.,n.d. Web. 22 Dec 2016.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atoms_for_Peace>

Moxie, M. “Atomic Age Design: Beauty and the Bomb”. Retropedia: A Look at Style and Design Through Time. 23 Jan 2013. Web. December 2016.

Philpott, Sarah. “St Nicholas: Naughty or Nice?”. The History Vault. N.p.,n.d. Web. 22 Dec 2016.

<http://www.thehistoryvault.co.uk/st-nicholas-naughty-or-nice/>

<http://revivalvintagestudio.blogspot.com/2013/01/mid-century-design-in-atomic-age-beauty.html>

Hine, Thomas. Populuxe. Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher. 1986.

Leave a Reply